“Declination: A Noun. The horizontal angle between the true geographic North Pole and the magnetic North Pole, as figured from a specific point on the Earth.”

|

Declination is a term that causes “brain cramps” for many of my students in my map and compass classes. When I mention Magnetic Declination eyes roll.

The web site www.magnetic-declination.com has an excellent discussion of what declination is and what causes it:

“Magnetic declination varies both from place to place, and with the passage of time. As a traveler cruises the east coast of the United States, for example, the declination varies from 20 degrees west (in Maine) to zero (in Florida), to 10 degrees east (in Texas), ......the magnetic declination in a given area will change slowly over time, possibly as much as 2-25 degrees every hundred years or so.......... Complex fluid motion in the outer core of the Earth (the molten metallic region that lies from 2800 to 5000 km below the Earth's surface) causes the magnetic field to change slowly with time."

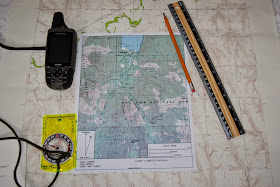

Land navigation is based on the relationship to the North Pole; also known as “true north. The measure of degrees of direction in relation to true north is called “degrees true.” Maps are laid out in degrees true. Land features (buttes, mountains, streams) on a topographic map are in reference to degrees true. By that I mean the bearing from one mountain peak to another will be referenced in degrees true. The map below illustrates that point.

Magnetic compasses do not point to true north (the North Pole); the magnetic needle points to an area that could be considered the magnetic North Pole.

As illustrated below, declination data can be found in the diagram at the bottom of a USGS topographic map, (on some commercially produced maps it can be hard to find.)

Because declination changes over time, I recommend that map declination information be verified at www.magnetic-declination.com. This is essential in the Pacific Northwest where maps are notoriously out of date in terms of road, and city data.

So, how do we make this simple? How do we convert magnetic to degrees true?

I could do the math. In Oregon, where I live, the magnetic declination is 15.6° East declination.

My recommendation: have the compass do the work so that there is no confusion with the math.

To do this, I need to choose a compass that can be adjusted for declination. Some examples are the Silva Ranger or the Suunto M3.

With one of these compasses, the compass dial or housing is adjusted and rotated manually. Both the Suunto and Silva Ranger come with a small, flat adjusting tool. Consult with owner’s manual that came with the compass.

If declination is Easterly (Western U.S.) I will rotate the dial causing the baseplate’s orienting arrow to move in a clockwise direction.

If declination is Westerly (Eastern U.S.) I will rotate the dial causing the baseplate’s orienting arrow to move in a counter-clockwise direction.

Now, adjust the dial and align the red magnetic needle on top of the orienting arrow (the red arrow engraved on the baseplate) the compass will provide directions in degrees true.